What is the best way to spot deception? It is one of the fundamental elements of interviewing. But how effective are standard procedures at the border, and can machines do a better job of it than people? A Frontex research project with the Royal Dutch Marechaussee (the Dutch Military Police/KMar) sought answers to these questions and more in September 2012.

News

Spotting Deception: Man against Machine

2012-11-13

The team conducted a simulation exercise in order to better understand how border guards take decisions in a scenario of “unknown threats” (i.e. no database hit, no fraudulent documents). The exercise was part of a broader research project aimed at studying the effectiveness of first-line border control in making the right decision when sending passengers to the second line for more detailed questioning, and the factors that affect performance.

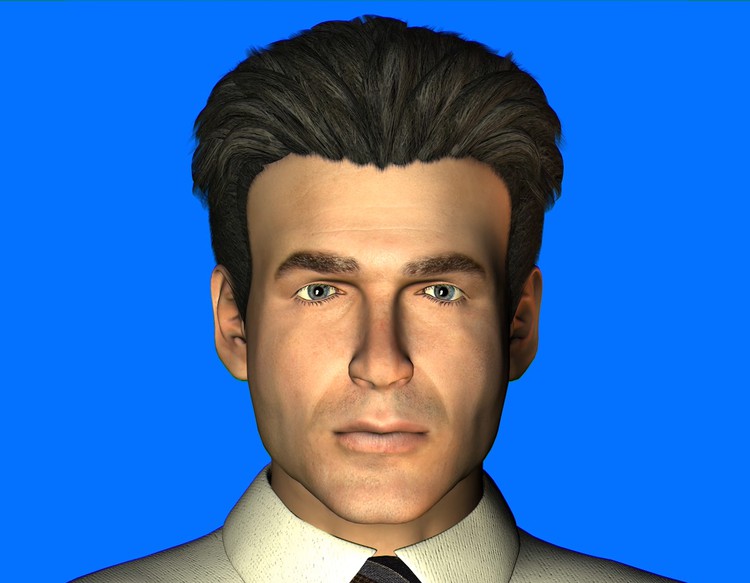

The exercise took place at the KMar Border Security Training Centre in Apeldoorn and pitted the skills of border guard experts from 14 Schengen Member States performing spotting, first- and second-line checks against an automated deception detection system. The “Avatar” system (Automated Virtual Agent for Truth Assessments in Real-time) was developed by the Borders project at the University of Arizona. It is a prototype system resulting from research in contact-less sensors, decision support, and deception detection. The goal was to correctly identify threats based on a given scenario and profiles distributed during a briefing. The aim was to better understand what makes border guards suspicious (what physio-behavioural cues border guards pay attention to in order to make a quick decision), how the machine performs in assessing credibility, and whether border guards can make better decisions with the help of the machine.

The scenario

A hypothetical Joint Operation (JO) called “Champions League 2012” was designed, closely following the model of the real JO Eurocup 2012. The scenario saw two Dutch teams — Ajax Amsterdam and Feyernoord Rotterdam — having both qualified for a Champions League Final match to be held at London’s Wembley Stadium. The scenario involved the risk that suspected hooligans (not on the watchlist) would try to mix with real Dutch supporters to attend the match. In addition, a specific Dutch hooligan group was suspected to have joined forces with a British neo-Nazi movement and to be using the match as a cover to enter the UK and attack an important international governmental meeting on migration.

The role of passengers was played by KMar cadets/students, who were surveyed to assign them roles that most closely fitted their true personality profile (and any real team allegiances) to make their reactions as realistic as possible. The task of selected students was to lie when asked about which team they support. For example, if a student declared themselves to be an Ajax fan in the survey, he/she would be asked to play the role of a Feyernoord supporter. The rest of the students were not asked to lie and did not know the details of the scenario. In addition, four of the 29 were given additional information about the neo-Nazi group and the planned attack. Their task was to conceal information and, if asked, to deny they knew anything.

Information Vs Reactions

In the “human” group, eight of the 29 passengers lying and one in four of the “hooligans” concealing information were correctly identified and stopped by border guards in the second line. An additional nine were correctly suspected by the spotters and first-line officers and were referred to the second line but were subsequently released. This gives more or less an accuracy of 25 percent true positives. The avatar also interviewed the cadets and captured some 70-75 percent of the deceivers (also true positives).

A closer inspection of the processes at work is revealing. While border guards seemed to focus primarily on consistency of information, the machine was totally information blind focussing only on physiological-behavioural reactions including gaze, pupil dilation and voice changes. The exercise led to discussions on the role of technology in border checks, the importance of profiling and experience, and how subjectivity affects decision-making.