People smuggling in Africa is a major criminal operation that collects billions of euros every year from desperate people. Most depart from Libya and attempt to cross the Central Mediterranean, which is the currently the main entry point for migrants into the EU.

Information collected by Frontex paints a picture of an increasingly sophisticated illicit “business” spanning numerous countries that increasingly puts profit ahead of the lives of its “customers”. It involves many groups and militiamen who control different parts of the migratory routes across Africa. Data collected by Frontex about these routes have proven valuable in helping national authorities and Europol in their investigations of these criminal networks and has led to arrests of suspected smugglers.

The number of migrants who arrive in Europe via this route is steadily increasing. Most migrants try to reach Europe from Libya, which is the main departure country towards Europe with a well-established presence of smuggling networks.

The main migratory routes for people crossing the Central Mediterranean are the route from West Africa and another from the Horn of Africa.

On the routes from West Africa, the main migrant smuggling hub is the city of Agadez in Niger. Due to its location, Niger is the key transit country used by the migrants originating from West and Central Africa. Most migrants use regular bus lines to reach Agadez in Niger where they pay smugglers to first take them across the Sahara, and then from Libya to Italy.

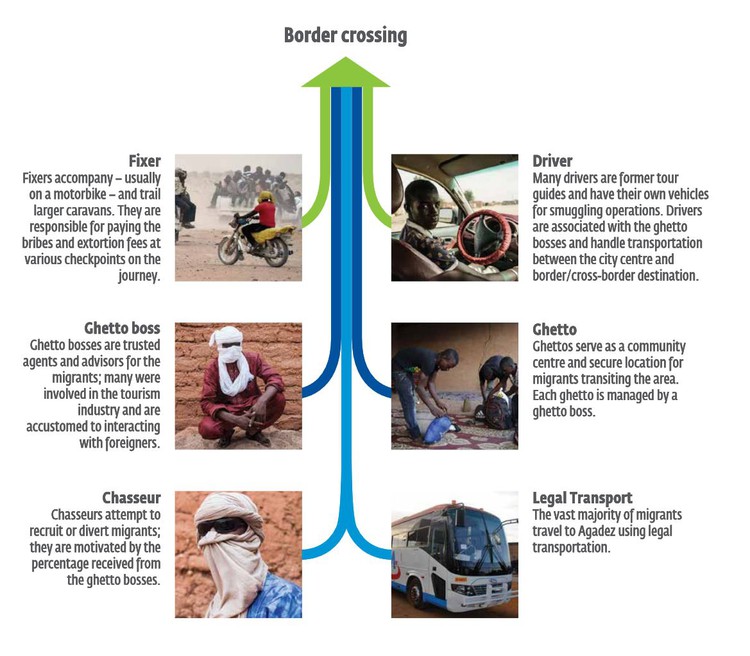

The many smuggling networks in Niger’s largest city usually enjoy support from the local community that sees economic benefits in the activities of the smugglers. This is especially important as people smuggling is an important source of income for a large part of the population of Agadez. On top of the hierarchy are ghetto bosses, who run temporary accommodation for migrants (so-called ghettoes); as well as fixers, drivers and recruiters, who are on the outlook for potential customers and who receive a cut from the ghetto bosses.

In Agadez, migrants contact people smuggling networks operating in the area who then arrange their journey further north. In between the different stops, migrants are accommodated in ghettoes across Niger, usually in mud-brick houses or closed compounds. Once there are enough migrants to fill a pickup, a ghetto boss calls a driver to move the migrants across the border to Libya.

The trip from Agadez to the coast of Libya can take two to three weeks if the migrant has the money to pay for all the legs of the journey, or several months if he or she needs to stop on the way to earn money to move on.

From Agadez, migrants are transported in pick-up trucks to Sabha, where those who have money to pay the facilitators move on to the coastal area and others stay to work, often in very difficult conditions, suffering abuse at the hands of the criminals. From Sabha, migrants can hire a local taxi or car to take them to Tripoli.

The trip can cost around 500 euros, a high amount of money for local standards, which is often collected by a whole family for one migrant’s journey. Migrants from West Africa usually use bank transfers to pay smugglers.

Money transfer companies partner with local vendors, allowing for transfers and bank activity via a computer or cell phone.

The trip from Western Africa to the coast of Libya can cost anything from 500-800 euros per person for a crossing on a rubber dinghy or a small wooden fishing boat. With people smugglers now putting as many as 160 migrants on one boat, the profits they make are enormous – they can pocket more than EUR 0.5 million from just one crossing of 400 people on a wooden boat.

Historically, most of the trade and smuggling takes place along the ancient caravan routes in the Saharan desert that have been operated by two nomadic groups – the Tuareg and Toubou tribes.

These two tribes control the main routes in Niger and Sudan on the border with Libya. The Tuareg and Toubou dominate the local human smuggling business as their clansmen are spread on both sides of the border.

Since the overthrow of the Gaddafi regime, Libya’s border security posts along the border with Niger have largely remained unprotected. The Toubou tribe has taken advantage of this void and established control over most areas providing access to southern Libya.

Many migrants from Sub-Saharan countries transit through Algeria to reach the border area with Libya. Here, smugglers help them cross the border, and also offer to transport the migrants to the departure areas in the west coast of the country.

The journey from West Africa to Niger is made easier by the free-movement protocol within the ECOWAS area, which covers 15 West African countries. This means that migrants who are headed for Libya can travel to Niger quickly and cheaply because they do not need visas to cross borders in the ECOWAS area.

Eritreans represent the main nationality on this route, followed by Sudanese and Somali migrants. Eritrean migrants are approached in their home country by Eritrean smugglers and taken to Sudan. Khartoum in Sudan is the main smuggling hub on this route.

The smuggling network in Sudan mostly consists of locals who take migrants to the border with Libya in private pickups. From here, migrants are transported by members from Tuareg tribes to coastal cities in Libya, from where they are taken to departure areas on the coast.

Migrants from the Horn of Africa usually pay for each leg of the journey separately. When it comes to payments, in Eastern and Sub-Saharan Africa the hawala system is often used - an informal way of transferring funds based on honour code. The hawalaoperates outside of traditional financial channels and relies on a network of trusted brokers. The journey from East Africa to Italy can take two to three weeks. It can be much longer if the migrants do not have enough money and must work along the way to earn funds for the rest of the trip. The total cost to reach Italy can amount to EUR 3 000. Some migrants use remittances from their friends of family members in Europe to cover the costs.

In the past two years Frontex has noticed worrying changes in the way smuggling networks operate that make the passage of the Central Mediterranean even more deadly.

Always seeking to maximise profits, smugglers are now forcing an average of 120-130 people on 10-metre rubber dinghies that just a couple years ago carried no more than 90 people. The boats themselves are made of materials of much worse quality than in the past. The criminal gangs involved in people smuggling often use threats and physical violence to compel the migrants to get onto the shabby dinghies. They also give the migrants on board less fuel, food and water, as they expect the dinghies to be rescued soon after they leave the Libyan territorial waters. Indeed, while in 2011-2013 the boats would regularly reach the Italian island of Lampedusa, 160 nautical miles (ca. 300 km) away from Libya, most of the rescues today take place close the Libyan territorial waters.

Currently, smuggling networks have been mainly based on Libya’s coast between the towns of Gasr Garabulli and Zuwara, and over 80% of the dinghies are boarded between the towns of Sabratah and Az Zāwiyah.

Frontex officers deployed in Italy interview migrants who have crossed the Central Mediterranean. These interviews are voluntary, and the information gathered provides valuable insight into the reasons for migration as well as the methods used by people smugglers. For example, interviews with migrants helped get information on people suspected of being involved in human smuggling. They have also improved the Frontex’s ability to map criminal networks operating in North Africa, Turkey, Italy and Greece, information which has proved crucial to investigations run by national police authorities.

With the new mandate, Frontex can also collect personal data of persons suspected of people smuggling, terrorism and other cross-border crimes, which it shares with national authorities and Europol.

For more information on how smuggling networks bring people to Europe, see our video: